Defining our constitutional crisis

How to use "checks and balances" to measure the health of American democracy.

The term “constitutional crisis” has become a popular phrase on social media, in op-ed pages, and even on the Senate floor. But defining “constitutional crisis” is surprisingly difficult. It’s ominous, but vague.1

After all, the U.S. Constitution provides a range from firm rules to undefined suggestions. For example, while it’s super detailed about the age you have to be to run for office, it’s less clear on how we should interpret “treason.”

This vagueness has the benefit of making a 237-year-old document (relatively) applicable to current-day political issues. But, it also makes it difficult to pin down whether or not it’s been violated. Whether or not we’re experiencing a constitutional crisis depends, first, on your definition.

I’m going to propose a relatively simple measure for the health of democracy—checks and balances. After all, this is the focus of the Constitution.2 Today, we’re going to consider how our system of checks and balances offers a straightforward way to define constitutionality. We’ll then evaluate how it’s holding up over the past month (spoiler alert, not great, Bob!).

What are “checks and balances”?

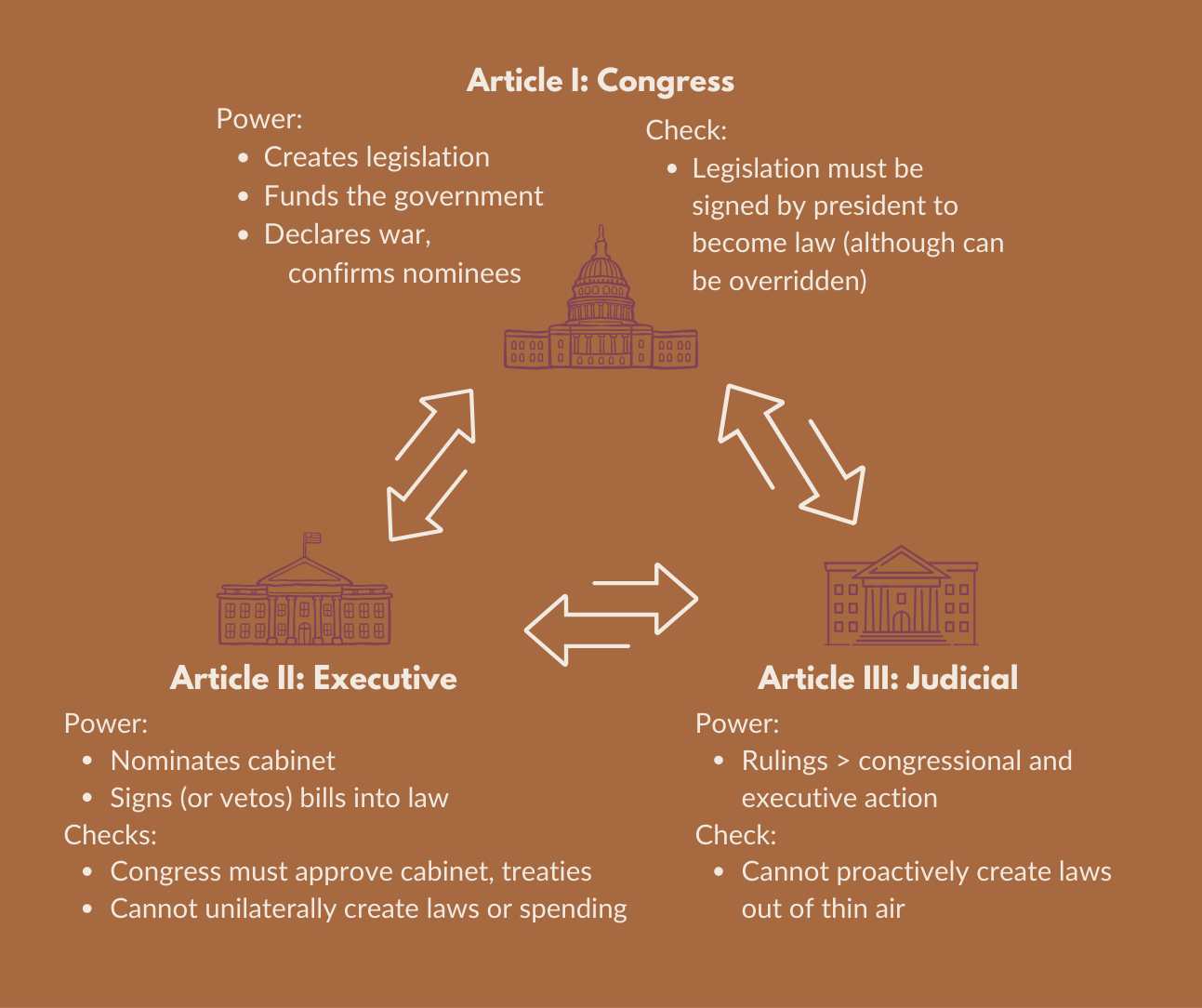

Unlike a monarchy (ruled by a King), or a parliamentary system (ruled by a legislature), American is governed by all three branches: the legislative branch (Congress), the executive branch (President and bureaucracy), and the judicial branch (Court system).

Determined to avoid an all-powerful monarch, the Founding Fathers delegated different responsibilities to each branch of government, as well as ways that branches could hold one another accountable. Think of it as a big game of paper, rock, scissors.

Each branch has both proactive powers and limitations. While there are many, today we’re going to focus on those particularly relevant to current events.

First, powers unique to each branch:

Article I: Congress is responsible for writing and passing legislation to become law (Section I), and providing the funds to implement these laws and programs (Section 7 and 8). We refer to these funds as appropriations.

Article II: The president can nominate his cabinet, but they must be confirmed by the Senate. The president is Commander in Chief, although entry into war must be approved by Congress (Section 2).

Article III: Unlike the other two branches, the court system doesn’t have inherently proactive powers—they cannot unilaterally act or create law. Their power comes from their ability to eclipse decisions made by the other branches through court rulings.

Second, each branch has ways to “check” one another:

Article I: The President can be impeached by Congress, and most major presidential decisions (war, treaties, cabinet appointments, agency creation) must be approved by Congress. Congress can also create a court system or pass an amendment that overturns a judicial decision.

Article II: For a congressional bill to become a law, the President must sign it. If he does not sign it, the bill is “vetoed”, and does not become a law. But! Congress, with 2/3 support, can override a presidential veto, making it a law.

Article III: The ultimate check. Any decision the judicial system makes about the legality (i.e., constitutionality) of a congressional or executive action has the weight of the law (Section 2).

This very brief overview should make two things clear: First, Congress has the greatest amount of responsibility. Not only are they responsible for writing and passing bills that can become law, they can check the president’s actions through impeachment, confirmation hearings, treaty reviews, and more.

Second, the President does not have the authority to unilaterally create a law. This also means that President does not have the authority to spend (or not spend) money that Congress has legally appropriated. And, louder for the people in the back: this means an executive order is not a law.

Impoundment, executive orders, and ‘DOGE’

So, with the constitutional basics in mind, let’s tie it back to the past month of executive action.

Impoundment is when the executive branch refuses to spend money that Congress has already appropriated. The argument is that even though Congress may appropriate funds, doesn’t mean they have to spend it.

Although the Trump Administration has tried to cut appropriated funds (ex: grants under the National Institutes of Health, USAID, Head Start Pre K programs, etc.), impoundment has long been deemed illegal and unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has ruled, for many decades, that if Congress appropriates the money—the president must spend it.3

The second thing the Administration is attempting to do is rule by executive orders, rather than law. In reality, executive orders are no more than executive branch memos, and they do not carry the weight of the law.

Several of Trump’s executive orders are him expressing his feelings about something or requesting executive branch employees to write a report4—that’s relatively standard. All presidents have used executive orders in this way. Others however, like ending birthright citizenship, are “blatantly unconstitutional.”5

But most of them strategically fall into a legal grey area. Congress has passed laws creating agencies and detailing how program should operate (like, USAID or the Department of Education). While those cannot be “deleted” though executive order, Congress does leave a great deal of decision-making up to the agency and executive branch. Legislation provides the framework and funding, but often allows the executive branch bureaucracy to fill in the details.

For example, Congress doesn’t include details on hiring needs or the scientific specifications of a regulation when they write legislation—and most of the time, we wouldn’t want them to! The experts who run these programs are in the best position to make these decisions. But this reality of lawmaking means that there are opportunities for executive-level directives to mold the bureaucracy.

The Trump Administration has spotted this vulnerability, and is testing the limits in new ways. This is best exemplified through the creation of Elon Musk’s ‘DOGE’. Although the President cannot unilaterally establish an executive agency (say it with me: that’s Congress’s job!)—the Trump Administration has circumvented this glaring legality by using the shell of an existing department—the United States Digital Service—to house DOGE.6

However, even with this creative caveat DOGE is still unconstitutional under the system of checks and balances: 1) the people working there haven’t been confirmed by Congress,7 2) we still do not know the source of their operating funds (executive branch funds must be appropriated by… Congress!), and 3) by shutting down programs and access to funds they’re making policy decisions that require an act of Congress.

So, is there a constitutional crisis?

In answering the question of whether or not we are experiencing a constitutional crisis, we have to first define constitutionality. And when the Constitution is clear—as it is about the case of checks and balances—that is where we can also most clearly understand if our democracy is at risk.

And in this regard, congressional checks and balances have already failed. Today, the branch intended to be the strongest is incredibly weak: the Republican-controlled Congress has abdicated its Article I responsibilities. Congress has not defended its appropriated funds, has passed all of Trump’s nominees, and has shown little interest in enforcing their own laws.8

To some degree, this isn’t entirely new. Congress has routinely failed to reauthorize programs, specify the usage of grants, pass appropriations laws on time, declare war, and approve treaties.9 But the Trump Administration is attempting to consolidate power in an unconstitutional and unprecedented way—and the Republican Congress is letting them!

We should view the executive-congressional relation as a canary in a coal mine. If other institutions give way in the same fashion, we are, to use a super-professional term, in deep shit.

Or, as Adam Liptak wrote in the New York Times earlier this week:

“There is no universally accepted definition of a constitutional crisis, but legal scholars agree about some of its characteristics. It is generally the product of presidential defiance of laws and judicial rulings. It is not binary: It is a slope, not a switch. It can be cumulative, and once one starts, it can get much worse.”

And while I generally try (try) to live by the advice: “don’t worry about something that hasn't happened yet,” there is legitimate reason for concern: Vice President JD Vance has advocated for ignoring the courts (unconstitutional), the director of the OPM (essentially the HR of the executive branch) has advocated for widespread use of impoundment (unconstitutional), and an executive order this week called for consolidating independent agencies (including that of elections commissions) under Trump (yes, unconstitutional).

Is there hope?

Of course! For one, the courts have consistently defended the Constitution thus far—and the White House has been largely responsive to the courts’ decisions.10 The Administration is also choosing to work in this grey area of executive orders—not outright illegality (birthright citizenship and ignoring due process for legal immigrants aside). But domestically, this indicates some willingness to maintain existing structures of checks and balances.

We should also remember why the Trump Administration is trying to govern by executive order: they know they can’t get the legislation they want through Congress (the Republican majority is historically slim, their policies are incredibly unpopular, and passing legislation is slow, by design!).

As Ezra Klein said, for most of Trump’s executive orders, the best course of action is “don’t believe him.” It’s good advice. Executive orders are not laws—and more states, executive agencies, universities, and most importantly, Congress should heed this advice.

But for us as individuals, understanding the levers of power is key to knowing where, and how, to channel our efforts. As Trump’s unpopularity continues to rise by the week, Congress may be inclined to act more. We must communicate with our elected representatives and pressure our members defend their turf. They work for you! You can start here and here and here.

Questions? Ideas?

P.S. Other issues of constitutionality

I think it’s important to mention two things, unrelated to checks and balances, but explicit in the Constitution, that Trump has breached.

Article II, Section 1 states, “The President shall, at stated Times, receive for his Services, a Compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during the Period for which he shall have been elected, and he shall not receive within that Period any other Emolument from the United States, or any of them.”

In other words, the President cannot profit off of his position. Trump has already made hundreds of millions of dollars off of a “meme coin” he launched directly before inauguration. Although he claims the funds are in a trust for his (adult) children, it’s still a personal profit.

Article II, Section 4 states that the President shall be impeached for treason.

Trump has said twice this week that he is above the law, even referring to himself as “the king.” Wasn’t that the whole point of the Constitution in the first place? But then again, the Founders envisioned a Congress that would actually follow it.

Which works to the Trump Administration’s advantage—as they “flood the zone” vague attacks can be harder to coalesce around (More here: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/28/us/politics/trump-policy-blitz.html).

Constitutional scholars and lawyers may disagree :)

This is a nice overview: https://www.npr.org/sections/planet-money/2025/02/18/g-s1-49220/trump-ignore-congress-spending-laws-impoundment

For example, EO “Expanding Access to In Vitro Fertilization” just requests that White House aides prepare a list of solutions to lower the cost of IVF within 90 days. No substantive policy changes here. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/02/expanding-access-to-in-vitro-fertilization/

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/another-federal-judge-blocks-trumps-order-ending-birthright-citizenship

Honestly, pretty creative, and somewhat similar to how Congress passes appropriations bills, but I digress.

Not all federal employees are subject to congressional approval. The number of federal appointments that are subject to congressional approval has varied overtime, but it’s more than just agency heads! Under secretaries, those requiring high levels of security clearance, and others are subject to appointment. Safe to say a DOGE employee accessing all of the country’s tax and social security data would be subject to congressional approval.

And of course, they didn’t impeach him after January 6th.

I have written extensively about this here, see Chapter 10: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRPT-116hrpt562/pdf/GPO-CRPT-116hrpt562.pdf

In some cases, the Administration has not reinstated funding as directed by the courts. Whether this is a purposeful ignorance of the court system, or a byproduct of haphazard coding, is yet to be seen.