Hi all, and happy Friday. I am so thrilled to share our first-ever guest post! My friend and Senate scholar, J.D. Rackey, will be walking us through the history and basics of the Senate filibuster.

For those interested in the judicial nomination process, following the retirement of Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, see here.

Filibuster 101

If you’ve been following the news lately (or even if you haven’t) you’ve likely heard endless chatter about the filibuster. The parliamentary procedure has become increasingly important to the policymaking process over the past decade, and the focus of so much ire of late.

But what is the filibuster, what are its origins, and how is it actually used right now?

This post will provide a brief overview of all of these things as well as a lengthy list of further reading—as is fitting for understanding a procedure so central to the “world’s greatest deliberative body.”

Origins

Where does the word filibuster even come from? It has been traced back to Dutch and Spanish origins meaning “freebooter” or “pirate.” In short, a filibusterer is someone who takes control of the chamber much like a pirate taking over and plundering a ship at sea.

But what is a filibuster in the Senate? There is no one consistent definition of the filibuster. Many scholars approach the topic in somewhat different ways. This is important to academics because how you define something determines how you measure it. But there is a general consensus that a filibuster is an act whose intent is to delay or prevent the consideration of a bill.

In the Senate, obstruction can, and has, taken many different forms over the years—but for the purposes of this discussion we can focus on the tactic of “talking a bill to death.”

While you could be led to believe by recent discussions that bills have always met their demise because they were talked to death, or, that the filibuster is a common occurrence throughout history, that is not the case. In fact, for most of the Senate’s history, filibusters were rare occurrences. They were rare because 1) they were viewed as egregious violations of the norms that governed how senators would treat each other and 2) they were typically ineffective at killing a bill in the long-term.

Things Changed

Eventually, for a host of reasons we won’t delve into here, the rate of filibusters began to pick up. The rate of filibusters increased so much that by the early 1900s the Senate became utterly gridlocked and President Wilson demanded the Senate develop a way to end debate on pending business because he was frustrated—like many presidents since—that his executive branch and judicial nominees were unable to be confirmed.

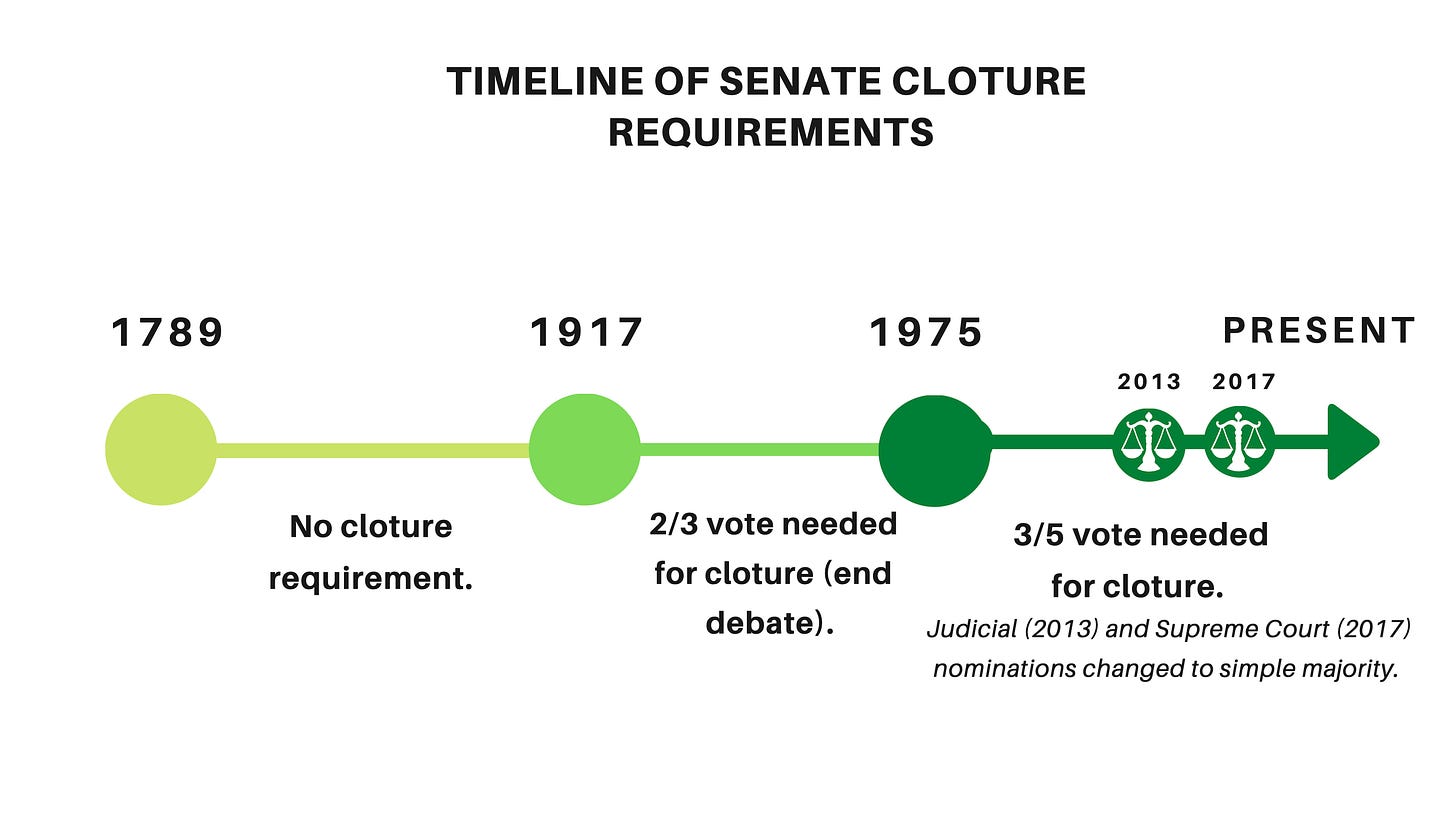

As the figure below shows, this is when the Senate introduced cloture to cut off excessive debate.

In 1917, when cloture was first adopted, even more senators (two-thirds) were needed end a filibuster than are needed today (three-fifths). Senators really like to protect their individual powers, and the power to speak as long as you want on the floor was one of the most revered and respected elements of the office. So, if the Senate was going to limit this power it should only happen if an overwhelming majority of senators agreed it was time for someone to stop talking.

This threshold was lowered to three-fifths of all senators in 1975, under circumstances similar to what we see today: important civil rights legislation that was highly visible to the public kept getting filibustered by Southern Democratic senators. So, Majority Leader Mike Mansfield lowered the threshold need to invoke cloture and end debate. He also formalized the “two-track system” that meant any bill being filibustered could be held to the side while other legislation could still move forward.

So, how does the filibuster work today?

Today, the filibuster does not require an actual “speaking” filibuster. Instead, it’s considered a first voting hurdle—senators must overcome cloture (three-fifths of Senators voting in the affirmative) to then begin the vote on the actual bill.

The result of the lack of speaking requirement, as well as the two-track system, is that number of filibusters has gradually (and more recently, rapidly) increased. The increased number of filibusters has crippled the Senate’s ability to conduct the business of the nation, forcing further changes to the cloture rule. While Figure 1 shows the big changes to cloture over the years, there have actually been hundreds of exceptions to the cloture rule since it was first created.

Increased use of the Filibuster

The two-track system, rising partisanship, and decreased civility norms have essentially created a situation in the modern Senate where every bill is considered to be filibustered and requires cloture to “end debate” and allow for a final vote on a bill. This allows us to more accurately rely on the number of cloture motions filed and passed as a semi-proxy for the number of filibusters that are occurring.

As the figure below shows, the increase in the number of cloture votes (read: filibusters) over the past decade is unprecedented!

Filibusters end for a variety of reasons other than cloture, and some filibusters take multiple cloture attempts to be cut off. So, when using cloture as a proxy for the number of filibusters, it’s important to remember that the true number of filibusters lies somewhere between the number of attempted and successful cloture motions.

So, what’s next?

Sky-high levels of obstruction by Senate Republicans have forced Senate Democrats into a situation where they held a debate on the Senate’s rules and attempted a vote revive the talking filibuster in order to move forward with their voting rights legislation.

The vote ultimately failed (this time), but it has become clear that supermajority cloture—and by extension the filibuster as we’ve known it—is on borrowed time. The public, and an increasing number of senators, are coming around to the idea that the arcane procedure as anti-democratic and believe that it should be ended.

Further Reading

-Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy by Adam Jentleson

-Filibustering in the U.S. Senate by Lauren C. Bell

-The Senate Syndrome: The Evolution of Procedural Warfare in the Modern U.S. Senate by Steven S. Smith

J.D. Rackey is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Oklahoma and serves as the American Political Science Association’s Public Service Fellow with the U.S. House of Representatives’ Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress.